Research

Contact Information

Mahoney Library

Saint Elizabeth University

2 Convent Road

Morristown, NJ 07960

Phone:

Main Desk: (973) 290-4237

Library Hours:

Mon-Fri 8am to 12am

Sat-Sun 2pm-12am

The library will be closed:

- Monday, September 1, 2015

- Monday, October 13, 2025

- Tuesday, November 11, 2025

- Wed-Friday, November 26-28 2025

- December 19, 2025 - January 4, 2026

Misinformation and Disinformation

Both misinformation and disinformation involve spreading untrue information. However, the motivations behind each are different - misinformation is unintentional and can happen when the author simply doesn't have the correct information, or is creating satire someone interpreted as true. Disinformation is intentional, and happens when the author knows the information is untrue and wants to mislead people.

There are seven types of false information identified by Claire Wardle and published by the Association of College and Research Libraries, listed from least dangerous to most dangerous as follows:

-

Satire or parody

- Humor used to critique or mock a person, viewpoint, or policy. An example of this

is the popular satirical magazine The Onion.

- Humor used to critique or mock a person, viewpoint, or policy. An example of this

is the popular satirical magazine The Onion.

-

False connection

- Headlines, images, and captions that don't support their content. A common example

of this is clickbait titles like "Top Ten Secrets Your Doctor Doesn't Want You To

Know"

- Headlines, images, and captions that don't support their content. A common example

of this is clickbait titles like "Top Ten Secrets Your Doctor Doesn't Want You To

Know"

-

Misleading content

- Information intentionally framed to present a biased opinion. A very common example

of this is using emotional or opinionated language to describe a topic, like "Spineless

Congress Bullied into Passing New Bill" or "Forward-Thinking Congress Passes New Bill

to Cement a Positive Future". A neutral, not misleading, headline would read "Congress

Passes New Bill on Infrastructure"

- Information intentionally framed to present a biased opinion. A very common example

of this is using emotional or opinionated language to describe a topic, like "Spineless

Congress Bullied into Passing New Bill" or "Forward-Thinking Congress Passes New Bill

to Cement a Positive Future". A neutral, not misleading, headline would read "Congress

Passes New Bill on Infrastructure"

-

False context

- Real information that has been separated from its original context. For example, a

real image that has been captioned with the wrong date or location.

- Real information that has been separated from its original context. For example, a

real image that has been captioned with the wrong date or location.

-

Impostor content

- Information that impersonates a well-known reputable source. This could be a social

media account that claims to be a government organization or political figure but

isn't verified or listed on the organization's official website. It can also be a

website that looks like the real thing, but has the wrong domain name (often used in scams)

- Information that impersonates a well-known reputable source. This could be a social

media account that claims to be a government organization or political figure but

isn't verified or listed on the organization's official website. It can also be a

website that looks like the real thing, but has the wrong domain name (often used in scams)

-

Manipulated content

- Content that was once real, but has been photoshopped, doctored, or filtered to create

a different perspective. This can include AI-generated images based on real photos.

Depending on the creator's skill level, this may be difficult to spot just by looking

at the image

- Content that was once real, but has been photoshopped, doctored, or filtered to create

a different perspective. This can include AI-generated images based on real photos.

Depending on the creator's skill level, this may be difficult to spot just by looking

at the image

-

Fabricated content

-

Completely false information, made up by the author and intended to deceive and harm. Most AI-generated content will fall into this category.

-

Additional Resources

Understanding Information Disorder

Keeping Up With Misinformation and News Literacy

Examples of fake websites

College of Staten Island LibGuide on Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation

Cornell University LibGuide on Misinformation, Disinformation, and Propaganda

Bias

Bias can be hard to spot, as authors generally present their writing as fact, not opinion. Sometimes an author can be biased without even realizing it (although reputable authors and scholar will have another person or group of people proofread their work for bias before publication). You might also experience confirmation bias, where the information you read only supports the opinion you already have, instead of challenging it or analyzing it. Here are some different places to look out for when evaluating something for bias:

Headlines

- The headline is the first thing you see of an article and is designed to capture your attention, so it should convey maximum information in as little space as possible. However, some headlines rely on a shock factor or emotional angle to get you to read the rest of the article, while others will imply how you should feel about the reported event

Photos, captions, and camera angles

- Someone's expression and background can heavily impact your impression of them. Pictures with unflattering angles and awkward expressions can be used to make fun of someone or imply their incompetence, while composed and professionally edited photos can be used to present someone as confident and qualified. The choice of background also plays a role - pictures of a crowded event imply that it was popular, while a relatively quiet area of the same event can be used to imply that few people attended.

Use of names, nicknames, and titles

- The choice of descriptors can affect how the audience feels about a person, event, or plan. For example, "felon", "business owner", "grandfather", "criminal", "wealthy", "cruel", "dog lover", "liar", and "elderly" can all refer to the same person, but the choice of which one to use affects how you perceive them.

Selection or omission of information

- This may appear in the details of a specific story, or in what stories are published in the first place. If an author is reporting on types of 911 calls, but only includes calls that require police, they are omitting all information about 911 calls that only require medical care or the fire department. This might lead to the impression that crime is more prevalent that medical crises or fires, as police only sometimes show up alongside ambulances or fire engines.

Placement

- Articles placed on the front page (or homepage) of a newspaper or news website are the articles the publisher wants you to see the most. Articles that aren't prominent when browsing the news may be less important - or the publisher may be trying to cover the story up

Choice of words

- This is the easiest to spot, and what people typically think of when it comes to bias. It involves using (often unnecessary) descriptive words to influence how you think about the content. Biased words can convey support, adversity, suspicion, approval, disapproval, excitement, disappointment, surprise, disgust, and more. It is important to note that articles on crime that use "alleged" or "suspected" are not meant to cast doubt, but to reflect that it has not yet been proven in court that the suspect committed the crime.

Choice of author and sources

- A long list of cited sources is generally a good sign when it comes to author credibility. However, if the author is trying to prove a point or argue for one specific side of an issue, they may only cite sources that agree with their stance. Consulted sources should be from a variety of perspectives and show all sides of an issue.

Data manipulation

- Data can be misrepresented even if the statements are technically true. The statement "hundreds affected by vaccine side effects" may be true, but that could be 350 people out of 1,000,000 vaccinated people - a mere 0.03%. A statement that more clearly evaluates the risk associated with the vaccine would be "3 out of every 10,000 people experience side effects following vaccination". The first statement is framed to imply that the vaccine is dangerous, or that there's an epidemic of side effects, while the second puts the number into context and gives the reader an accurate depiction of the chance they will experience a side effect.

Algorithms

- Algorithms govern what content is recommended to you on social media sites, YouTube, AI chatbots, and search engines. The more time you spend looking at a single post, video, or website, the more likely the algorithm is to suggest similar posts, videos, and websites. The code that controls the algorithm may be biased, or the data used to train the algorithm may have been biased. This can lead to an echo chamber and confirmation bias, where you are only fed information that agrees with content you've already seen.

Additional Resources

How to Detect Bias in News Media

University of Washington LibGuide on detecting bias

Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics

Identifying Misinformation and Bias

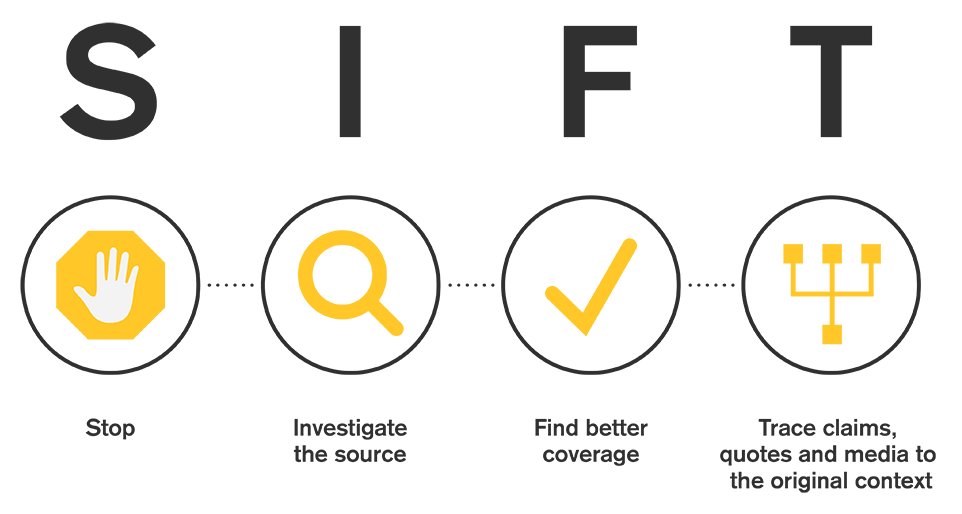

The best way to identify misinformation, disinformation, and bias is to read laterally. This involves reading multiple sources on the same topic to evaluate how well a source matches other information on the same topic. To do this, use the SIFT method.

Stop and reflect

This step reminds us to pause whenever we find ourselves caught up in an article or overwhelmed with source-checking tasks. When you first open an article or news story, think about where the information is coming from before you dive into it (especially if the tile is particularly clickbait-y). Do you know the website? What's their reputation?

Secondly, don't get overwhelmed with fact-checking every piece of information you read. While it is important to know where your information is coming from, you don't need to do a deep dive on every article. If you're just catching up on current events, reposting a story, or exploring an interesting topic, you probably only need to verify the publication is reputable. If you're looking to do deep research or write a paper, it's a good idea to locate multiple sources that confirm key information.

Investigate the source

This step has us looking at what the source actually is - who wrote it and who published it. The idea is that you want to know the background and goal of the source before you read it. An article about meat consumption in America written by the USDA may have very different goals than an article about meat consumption written by PETA. That doesn't mean one article is necessarily better or more factual than the other, but knowing the angle the author is coming from can help you decide whether the article is significant, trustworthy, and worth reading.

Find better coverage

This step is about finding other sources on the same topic. If you see a particularly outlandish or surprising claim, do a general search for the same information. For example, if you see an article claiming that having a pet cat is now illegal, you can search the web for "pet cat illegal" and see if any other articles pop up with the same claim, or if something entirely different happened and the original author was dramatizing. This step isn't so much about getting to the source of a claim - moreso about determining expert consensus on the topic. If 9/10 articles say that having a pet tiger is illegal, and the tenth article says that having any pet cat is illegal, you can probably surmise that the tenth article is exaggerating.

Trace claims back to the original context

Here is where you will investigate the original sources of information. Much of media has been stripped of its original context. It is extremely easy for people to omit important details or clip parts of a video to make it appear as if someone said or did something completely different.

For example, say you see a video circulating of a popular celebrity yelling at an innocent fan that wants to take a picture with them. From that video, you might think that the celebrity is rude and aggressive in general. However, in looking for the original source of the video, you find that the clip you saw cut out the scene right beforehand where the fan shoved the celebrity's child out of the way in order to get closer to the celebrity. That missing context makes all the difference in interpreting the video - the perspective shifts from an aggressive celebrity that hates their fans to a parent protecting their child.

The SIFT method was developed by Mike Caulfield and adapted for use at Saint Elizabeth University

Using The Onion as an example, here's how each step of the SIFT method would help

readers understand that the site is satire. Let's say you come across this headline:

"Bezos Wedding Guests Delighted By Amazon Worker With Ring Tied To Collar Crawling

Down Aisle", and are understandably shocked and confused. Click on each of the tabs below to

see each step of the process.

All of these steps on their own are enough to cast serious doubt on the truthfulness

of The Onion's article, but taken together we can say for certain that the entire

article was made up. The headline is written to spark outrage, the publisher has a

reputation for being satirical, no other sources confirm those claims, and we can't

verify where The Onion got their information.

Additional Resources

What "Reading Laterally" Means

University of Chicago LibGuide on Evaluating Resources and Misinformation

Fact-Checking

Here are some sites you can use to check facts and figures

- Politifact

- Factcheck.org

- Washington Post Fact Checker (requires individual Washington Post subscription; library access doesn't count)

- Snopes

- Truth be Told

- NPR Fact-Check

- Climate Feedback

- SciCheck

- Quote Investigator

- Ground News

- AllSides

Updated 7/23/25